The Religions in Egypt

According to the Constitution of 1971 and the constitutional declaration of Egypt, Islam is the official religion of the state and is practiced by the majority of the population of Egypt. There are no specific percentages of adherents of beliefs for Egypt, as official Egyptian statistics have stopped mentioning the number of followers of religions and sects since the 1996 census.

Throughout the Egyptian historical statistics of population censuses, the percentage of Muslims was estimated at an average of 94% and the percentage of Christians at an average of 6% until the 1986 census, where the last official census reported the number of adherents of different religions in Egypt.

As for the Islamic religion, its adherents in 2009, according to some sources, are estimated at 94.6%. While sources are estimating their percentage at about 90%, most of them are Sunnis and Jamaat, the Shafi'i, ash'ari and Hanafi sects are widespread throughout Egypt, and some of them belong to some Sufi ways, and most of the azharis from Shafi'i belong to the school of ash'ara speakers, there are also Muslim MU'tazila, Shia Imami and Ismailis, but there is no official census of them. Some sources estimate the proportion of Muslims to be between 80: 90% due to the uncertainty of the number of Christians.

Christian religion,

Similarly, the followers of the Christian religion are estimated between about 5.4% and about 6%. in September 2012, the number of Christians reached 5 million and 130 thousand, according to official statistics from the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics, while American sources say that they are 10% of the population of Egypt, 90% of them are Orthodox, including Catholics and evangelicals, and there are also parishioners of the Syriac, Roman and Armenian churches. This is the largest gathering of Christians in the Middle East. While the last official census estimated them at two million Christians and 800 thousand; estimates of Christian clergy differed about the number of Christians in Egypt, where Anba mark-the head of the Information Committee of the Orthodox Church - claimed that the number of Christians in Egypt reaches 12 million people, and Mark Aziz, the priest of the suspended church, said that the number of Christians in Egypt reaches 16 million Christians, while the head of the evangelical community, Reverend Ikram Lami, described these figures as exaggerated, as the number of Christians was estimated at no more than 10 million according to his opinion. Later, Pope Shenouda stated that the number of Christians was 12 million, a position contrary to his usual policy of not authorizing Christian censuses, which led some sources to question this figure, estimating the number of Christians to not exceed eight million. While the real figure is uncertain, some sources say that their percentage ranges from 10 to 20%. While sources estimate them at 15%.

It is not possible to determine the percentage of Christians in Egypt and the overwhelming majority of them are believers of the Coptic Orthodox Church with the presence of various minorities from the Patriarchate of Alexandria to the Greek Orthodox, Latins, Maronites and others; the last national census in the country observed the percentage of sectarian representation and did not include the diaspora, and the Church recognizes it was done in 1966 during the reign of Gamal Abdel Nasser, then the statistic stated that the number of Christians is about two million out of 29 million, i.e. by 7.2%, rising to about 9% by adding the Copts of the diaspora, the following statistic in 1976 challenged its validity, especially a period of tension between the Patriarchate of Alexandria and the regime of Anwar Sadat, as he stated that the number of Copts is 2.2 million, that is, compared to the previous census, the number of Copts has not increased The Christians of Egypt for a decade have only 200 thousand inhabitants, compared to a general increase in the population of Egypt estimated at six million, although the Christians of Egypt have no immigration problem in the sense spread in the Levant and Iraq, as well as no problem in having children. A 2010 Pew Research Center study suggests that the decline in percentages is mainly because, for decades, Christian birth rates have been falling in comparison with Muslims. The study also indicates that the number of Christians in Egypt may have been reduced in censuses and demographic surveys. According to the August 2011 Pew Forum report "Increasing Restrictions on Religion," Egypt has significant government restrictions on religion, as well as very high social hostilities. These factors may lead some Christians, especially converts from Islam, to be wary of revealing their faith. Government records may also reduce the number of Christians.

The last census that also included the sect took place in 1986 and showed that the percentage of Christians was 5.9%, about 2.8 million out of 48 million Egyptians at that time, based on this statistic, some civil associations and political parties still assess the percentage of Christians in Egypt, specifying that the current number out of 80 million is about 4.5 - 5 million people, but many independent bodies accuse the regimes of Anwar Sadat and Hosni Mubarak of manipulating the statistical ratios for political and social gains, and several international statistical studies determine the percentage by about 10% of the population, i.e. 8 million Egyptians out of 80 million; the World Factbook, together with the U.S. Department of State in the report on religious freedoms for 2007 said that it is difficult to determine the number of Christians inside Egypt, but it ranges between 6-11 million Egyptians, i.e. between 8-15% of the total population.

According to the Believers in Christ from a Muslim background: Global Census, a study conducted by the American University of St. Mary in Texas in 2015, about 14,000 Egyptian Muslim citizens converted to Christianity. Major General Abu Bakr al-Jundi, head of the General Mobilization and Statistics Authority, stated in December 2011 that the number of Christians in Egypt is decreasing from census to census, and their percentage may reach 5% of the population, due to the tendency of Christians to migrate out of Egypt more compared to Muslims due to their lack of exposure to the phenomenon of Islamophobia, to which Muslims are exposed, especially in Western countries.

Other religions,

There are about 200 Jews in Egypt. They are the remnants of one of the oldest Jewish communities in the world, which included the majority of Karaite Jews, along with rabbis and noorites; most of them emigrated with the beginning of the Arab-Israeli conflict in the mid-twentieth century.

There are also about 2,000 Baha'is in Egypt.

There are also Egyptians who identify themselves as non-religious, but there is no census of them.

Religious institutions,

There are two religious institutions in Egypt, one of the oldest and most important institutions for the Islamic religion represented by each of them:

Al-Azhar was built by the Fatimids to spread the Ismaili doctrine in North Africa before Saladin turned it into a Sunni University to become one of the most important pillars of Sunni Islam in the world.

Dar Al-Ifta, which was founded in 1895 and is headed by the mufti of the Egyptian Diyar, and this position is currently held by Sheikh "Shawqi Ibrahim Abdul Karim Allam", is the mufti of the Egyptian Diyar, in addition to being a professor of Islamic jurisprudence and Sharia at Al-Azhar University "Tanta branch".

The Coptic Orthodox Church, which is one of the oldest Christian churches in the world and one of the first five churches, and the Church of Alexandria is the seat of the one who sits on the chair of St. Mark, who is the pope of Alexandria and the patriarch of the preaching of St. Mark, and the current pope is Pope Tawadros II.

If Egypt has often been referenced by historians as ‘the Cradle of Civilization’, it has probably one of the most complicated religious aspects in entire human history. The fertile banks of the Nile did host agriculture, but they also produced a vast culture, where religion permeated every single aspect of everyday life, politics, and social order. From the earliest days of ancient Egyptian civilization up to this day, despite being primarily a desert dry land, Egypt has been a melting pot of different religions, starting from polygamy to finally embracing monotheism.

In this piece, Section II, How We Were: Reflections on Egyptian History, From Ancient Polytheism to Christianity & Islam, will be reviewed and analyzed, as well as the role of religion in the lives of the Egyptian population.

As a society, it can be said that religion was the foundation of ancient Egypt. The ancient Egyptians worshiped as they knew that everything from the annual flooding of the Nile to the cycle of life and death was not only natural but controlled by some divine power. This was a belief characterized by a multiplicity of deities, all of whom were in charge of a specific facet of existence and/or nature.

The Major Gods and Goddesses

Ra (or Re): Revered as the God of the Sun, Ra has been depicted as the most potent deity in ancient Egyptian religion. It was believed that Ra inhabited the sky during the day, providing light to the earth, and resided in the underworld at night. He would oftentimes be portrayed with a falcon’s head and wear a sun disk on top of his head.

Osiris: Osiris was an Egyptian death and resurrection god and held a significant place in Egyptian mythology in representing the concept of life as a cycle of birth, death, and resurrection. The Osiris myth and his resurrection, in the capable hands of Isis, his wife, became the pillars of the Egyptian afterlife experience.

The goddess was immensely popular and powerful. She was a protector of motherhood, magic, and fertility. Her protective aspect and the ability to bring Osiris back to life made her worshiped.

Horus, the god of the sky and of the king, is often shown as a hawk. He was also known because of his rivalry with the chaos god Set for dominion over the land of Egypt, which represents the struggle of order and chaos.

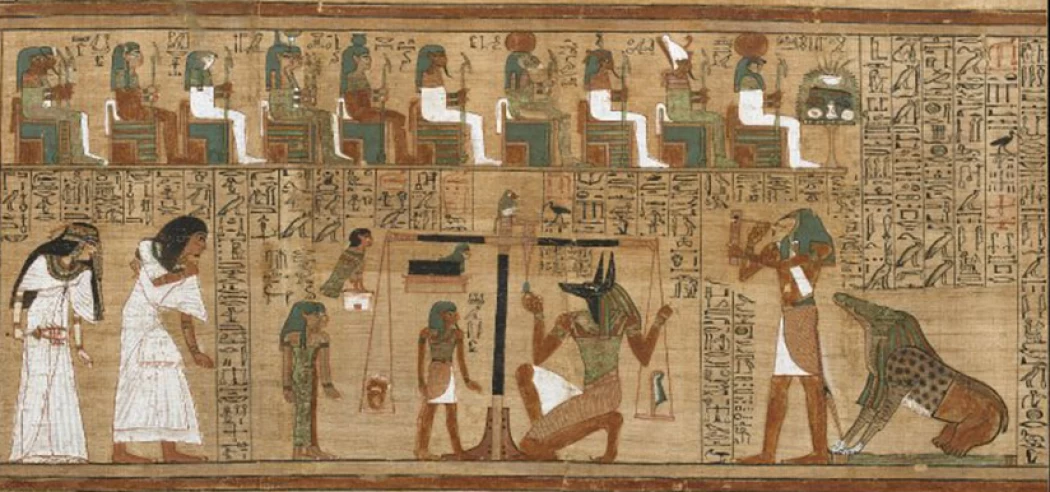

Anubis is the Egyptian god associated with funerary rites and the protection of the dead. He had the important task of supervising the ceremony of the heart's weighing, which assessed a person’s spirit in the next world.

The gods were not distant or abstract figures; they were present in every facet of life. Egyptians built temples across the country, conducted elaborate rituals, and offered daily prayers and sacrifices to ensure the favor of the gods and maintain ma’at—harmony and order.

Worship wasn’t the only reason for building temples; these structures were believed to be the earthly homes of the gods. The pharaohs had enormous temples like Karnak and Luxor built to worship and carry out rituals for the gods as well as to showcase the power of their rule over the land. No one was permitted to enter the temple’s most sacred, innermost areas except for the priests, who were thought to be the only ones capable of interacting with the gods.

Priests offered meals, incense, and prayers to the gods on a daily basis, performing their duties towards ensuring the gods’ continuous provision of security over the land of Egypt. These clergymen were very powerful and at times even had political authority as they helped the pharaohs in religious affairs.

For the Ancients, death was not a permanent end; there would be life after death. This notion fueled the people’s efforts to focus on death and think about how they would prepare in the appropriate way for their journey to the underworld, which in their minds was not an easy place to reach but one that guaranteed everlasting bliss as long as the challenges were overcome.

Mummification and the Preservation of the Body

Mummification was pivotal in shaping the Egyptian view of what happens when one dies. The body was to be maintained so that the ‘ka’ (or soul) would remember and go back to its residence after death. Mummification came to be practiced with a set of procedures that included arts of organ procurement, chemical treatment, and linen envelopment of the entire body.

A process of putting up preparatory arrangements for one’s afterlife would also include making tombs, which would have items that the dead person would require, such as food, clothes, and upright ‘ushabti’ figures meant to depict servants. The magnificence that royal burial places such as the Giza pyramids and those in the Valley of the Kings display indicates the extreme measures taken to ensure adequate rest and healthcare for the leaders when they die.

The mummification custom was bound to the Egyptian people's love of the afterlife. Bodies had to be maintained in a way that allowed the spirit, or 'ka', to identify it and be able to go back in after death. Mummification came to be seen with specific practices, which included the arts of organ downsizing, substance drying, and body plastering with bandages.

Another aspect of preparing for eternity was that of constructing tombs containing the essentials for the deceased, such as an abundance of food and clothes and miniature statues of servants known as ushabtis. Such an adulation can be seen from the wonderful construction of royal burial sites such as those surrounding the Great Pyramids of Giza and along the Valley of the Kings, where endless hope lies for the reasonable resting of the leaders within the period of their deaths.

The “weighing of the heart” ritual is one of the key convictions regarding the hereafter. In Egyptian cosmology, when a deceased individual was brought to the land of the dead, the god Anubis was tasked with weighing the heart against the feather of Ma’at, the deity representing truth and justice. Where the scales tipped in favor of the feather, the individual was considered fit to take his place among the dead in the other world. If the heart tipped the scale against the feather, then due to some impertinent act or lie, that heart would be consumed by the ferocious goddess Amit and the essence would no longer exist.

3. The Introduction of Monotheism: The Amarna Period

Throughout the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten, also known as Amenhotep IV, which was between the years 1353 and 1336 BCE, many changes were witnessed, especially in Egyptian religious practices. Akhenaten believed there was only one God to worship, and that was Aten, the sun disk, and he promoted the worship of Aten only. He constructed a new city called Akhetaten (Amarna, modern) and concentrated on the worship of this one god, excluding completely the rest of the traditional deities in the Egyptian pantheon.

The extent of how long this extreme change in religious practices lasted is very minimal. After the death of Akhenaten, the former worship of many gods was reinstated by the administrations that followed him, particularly through King Tutankhamun, and the cult of Aten was, for the most part, expunged from history. Still, the issue of Akhenaten's obsessive tendencies concerning religion remains a curious page in the story of religions in ancient Egypt. It demonstrates how potential changes in religion can be such a threat even when a rigid system is in place.